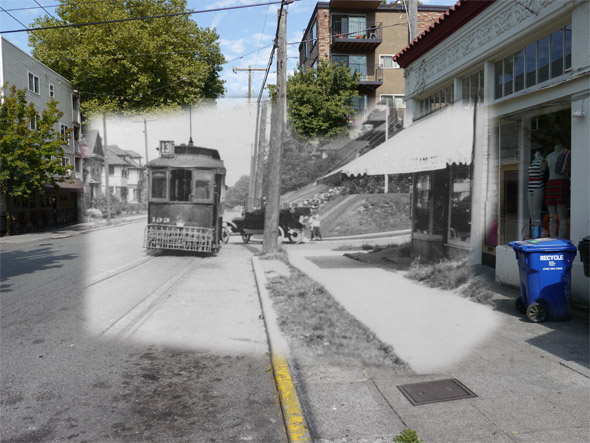

Somebody decided to put a streetcar here. Somebody invested in real estate. If you’ve got a business in the Summit neighborhood (looking at you, Top Pot Doughnuts) – you didn’t build that.

Somebody decided to put a streetcar here. Somebody invested in real estate. If you’ve got a business in the Summit neighborhood (looking at you, Top Pot Doughnuts) – you didn’t build that.

In Part 3 of On the Summit Line, we explore the overlooked plan to topple Seattle’s streetcar barons… and discover how it inspired much of Capitol Hill’s transit infrastructure.

In the series’ first installment, we learned of a gifted young woman who lived at the base of Capitol Hill in 1900. Part 2 described how she moved as a newly-wed to the Summit neighborhood, where Summit Slope Park is today.

This chapter is a bit of a digression. It should have been a short paragraph summing up the extensive literature on the failed 1906 Seattle municipal streetcar plan. Unfortunately that doesn’t exist. So instead we need to address this small business right now, investing in a new infrastructure for the historians of the future.

Rage Against the Machine

At the end of the 19th century, the Progressive movement arose in opposition to the theory of Social Darwinism. One of the things that they fought most fiercely was economic inequality and the amassing of monopoly power. After the Boston firm Stone & Webster bought up all of Seattle’s independent streetcar lines from 1899 to 1901, their holding company Seattle Electric Company became the embodiment of the machine that the Progressives raged against.

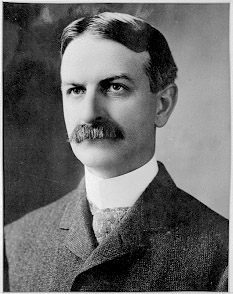

W H Moore, 12276 (SMA)

W H Moore, 12276 (SMA)

We’re Not Gonna Take It

After watching corporations take monopoly control of basic services like water supply, gas, electricity, telephone, and street car services in cities across America, a new idea emerged among Progressives. If it was okay for a private monopoly to strangle-hold the public, why wasn’t it okay for a government monopoly to better serve people’s needs?

In June of 1905, the Seattle Republican ran a front page headline “MUNICIPAL OWNERSHIP THE SLOGAN”. Halfway through the page-and-a-half rant, the editors wrote:

“Seattle cannot afford to allow private corporations to fatten off of the profits made in the private ownership of the public utilities… The city cannot stand back when all the civilized world has realized the necessity of municipal ownership.”

At the next mayoral election, the newly-formed Municipal Ownership Party’s candidate easily beat the Republican. William Moore’s single-issue platform was to put a streetcar plan in front of voters.

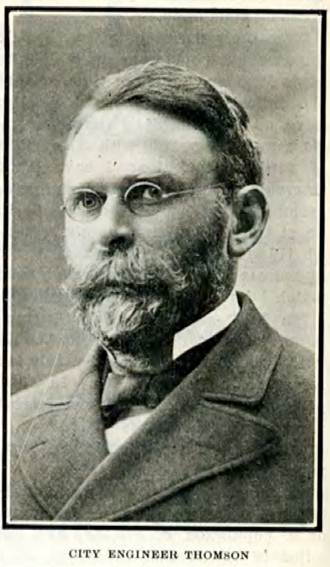

R. H. Thomson (Pac Building &Engineering Record, 8/4/1906 p3)

R. H. Thomson (Pac Building &Engineering Record, 8/4/1906 p3)

Cold, Hard Mathematics

Moore immediately tasked city engineer R. H. Thomson with creating a plan for a municipal streetcar system that would not lose money.

Thomson needed a data-backed analysis of unmet demand for streetcars and how much to invest in the system. After all, he couldn’t just say he’d build 9 lines of 9 miles and charge 9 cents a ride and expect some sort of 9-9-9 Plan to be successful.

Of course this was 1906. There were no databases or analytics packages. No GIS or block-level demographic information.

Thomson did have one tool: the recently published 1905 streetcar report by the U.S. Census Bureau. He looked at data from cities around America, and decided that Seattle should be able to support one mile of streetcar track per 1430 people. There was only one mile per 1750 people in 1906, which he took to mean a 25% gap of demand that could be filled.

Thomson hired the engineering firm of Hanford & Blackwell to double check his work. They considered statistics such as boardings per person per year and miles of track per square mile and came to a similar conclusion.

After Thomson had run the ‘rithmetic, his plan proposed a phased build out of a 56 mile system to poorly served areas of the city. It would reach Green Lake, Georgetown, Magnolia, the UW, Rainier Valley and Ballard. The system included a new tunnel under University Street from First to Pine, an elevated railway along the waterfront, and a new cable car on Denny from the water to Summit.

It was silly math by today’s standards. But in 1906, Thomson could sincerely say he had a “cold-blooded, mathematical basis” for his plan.

The plan and its municipal bond funding were placed before voters in September of 1906.

We Own This City

The Seattle Electric Company was not a fan. With no restrictions on corporate financing of elections, SEC embarked on a massive, stealthy campaign.

Their basic counter-argument was laid out in the Seattle Times in early August, after details of the plan were announced:

“Thomson proposes to spend $7,500,000 to build a street railway to run along the side of one which is already built, charge the entire expense to the taxpayers, and still demand five-cent fare.”

The Times, which had earlier been antagonistic to SEC, set out on a daily finance lesson for its readers with ever-more complicated analysis of the impact of the bond measure.

They also began publishing opinions by members of the Seattle Economic League (SEC’s front in the election) word-for-word. Realtor J. R. McLaughlin (*) warned:

“Seattle is a favorite throughout the whole United States. Money is flowing to this city from all sections of the country. We should not convey to the world that the voters of Seattle are hostile to the interests of invested capital. Capital is notoriously sensitive… Let [municipal ownership] alone. It is a delusion and a snare.”

The relentless economic arguments resonated with voters. They were convinced that the city could not carry the debt. On September 12 the vote failed by 15%.

(* McLaughlin appeared in CHS Re:Take #7.)

If It’s a Legitimate Plan

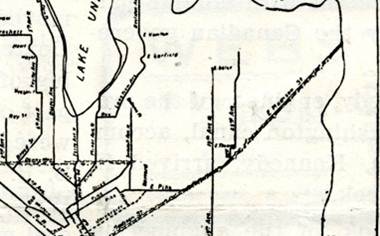

Streetcar plan Capitol Hill detail ( (Pacific Building &Engineering Record, 8/4/1906 p3)

Streetcar plan Capitol Hill detail ( (Pacific Building &Engineering Record, 8/4/1906 p3)

Besides poor economics, the League members argued that the municipal system would be a failure because the proposed lines were useless.

But SEC was talking out of both sides of its mouth. At least in a few cases, in order to win votes it made a corporate-personal pledge to build the proposed lines after the election.

On Capitol Hill this led to a huge expansion in service.

SEC connected the Broadway Line to the Brooklyn Bridge (now University Bridge) in early 1906 in the lead-up to the election. This is now the Metro 49.

In 1909, streetcars followed the proposed route on 23rd, continuing down the hill to the UW. This is now the Metro 43.

Construction started right after the election on two local routes. For the longer of the two, cars ran up Madison and then 19th to Galer. This is now the Metro 10 12.

The shortest was a little loop that went up Pine and then over Summit and back on Bellevue. This is now the Metro 14.

Each triggered a new real estate boom and created new neighborhoods across what would collectively become known as Capitol Hill. And they were all first mapped out for Thomson’s failed municipal streetcar.

SEC’s Summit Line ca 1910, LS0146 (KC Metro Files)

SEC’s Summit Line ca 1910, LS0146 (KC Metro Files)

Next Time We Wrap it Up

The Summit neighborhood didn’t appear out of nowhere.

Somebody planned the streetcar line. Somebody built it.

Somebody promoted the real estate. That was our man L. N. Rosenbaum, whose new realty business placed him in perfect position to become the key investor and promoter of the neighborhood.

We’ll learn about that next time in our conclusion of On the Summit Line.

Credit

Thank you to Dotty DeCoster for finding the map of the streetcar plan and SPL’s Bo Kinney for scanning it. Thanks to Richard Wilkens for pointing me to the plan’s enabling ordinance.

Upcoming

Rob will speak about early Capitol Hill history on October 25th at the Capitol Hill Library, 6:30-7:30pm.

In case you missed them, here are the last few Re:Takes on CHS:

Great article! It’s interesting to know the political story behind the streetcars.

Just a couple small corrections on Metro route numbers:

– Madison – 19th – Galer is the 12, not the 10

– Pine – Summit – Bellevue was the 14 until yesterday, now it’s the 47

David, nice catch on the 12.

In my defense, when I wrote this article, the 14 was still the 14. But am I comatose or something? Former transit activist, ride the bus up or down Pike/Pine daily, but I’ve never heard of the 47. And I’m scared look it up.

The 14 now goes from Mt. Baker through downtown and continues up 3rd Ave past Pike St into Belltown. The 47 now starts at 2nd & Pike and goes east and then north, following the same route as the 14 used to. The map is here: http://metro.kingcounty.gov/cftemplates/show_map.cfm?BUS_ROU

The 47 now spans only about 2 miles, shorter than just about any Metro bus route I’ve seen or ridden.

Thanks Jason. Too bad they didn’t number the new Summit bus #13, like in our photo. (Here’s a larger copy if you can’t see the sign http://www.flickr.com/photos/tigerzombie/7288918084/ )

There is already a bus #13. Some #2 buses change to a #13 as they enter downtown from their Union St. westbound route.

Thanks for the bus route schooling.

Metro doesn’t seem to know what the #13 is, so we should just reuse it… if you go to their 13 schedule it says that it goes to Madrona. But the map is just for downtown and Queen Anne: http://metro.kingcounty.gov/tops/bus/schedules/s013_0_.html vs http://metro.kingcounty.gov/cftemplates/show_map.cfm?BUS_ROU

‘splain that one!

I’ve never understood the point of it, but coming westbound on Seneca right as they cross into downtown the driver stops, gets up, and changes the #2 to a #13. Then it continues on. I think some of the buses go all the way to SPU, and some of them turn around before (I think at Seattle Center). It’s always seemed like a bizarre practice. Maybe there’s something I’m not getting, but it’s basically a #2.

The 13 goes to SPU. The 2 doesn’t.

Great article. I’m fascinated by the similarities between the streetcar routes and today’s bus lines, and the interplay between transit and real estate. This post does a great job of laying this out.

One thought: part of the reason why the routes have stayed so similar is that many of the street railway routes were converted to trolleybus routes. I would imagine that trolleybuses, like street railways, have some level of permanence because of the infrastructure involved in the route. Rerouting a trolley bus or a streetcar requires laying new tracks or installing new electric lines.

Seattle DOT has a great page showing a series of streetcar and trolleybus routes which shows the remarkable continuity:

http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/transit_history.htm