It’s just an ordinary, peaceful snapshot of a place we all love, taken a century ago. But it comes with a date scrawled along the bottom, allowing us to try for a moment to bring life to the thoughts of the strollers and promenaders in Volunteer Park that day.

It’s just an ordinary, peaceful snapshot of a place we all love, taken a century ago. But it comes with a date scrawled along the bottom, allowing us to try for a moment to bring life to the thoughts of the strollers and promenaders in Volunteer Park that day.

So much is missing. Isamu Noguchi’s sculpture Black Sun was installed in 1969. Left of frame, the Art Deco art museum was not built until 1933. Here and there small saplings are seen, and now they completely dominate the park experience and block out the stately water tower.

It was Sunday, May 30, 1915. Late afternoon, judging by the shadows. A woman stands at the far side of the fish pond, posing for her partner’s camera. Here and there couples are wandering together, perhaps discussing the day’s events.

Unknown photographer, scanned and uploaded by author to Flickr.

Instituted and Ordained By God

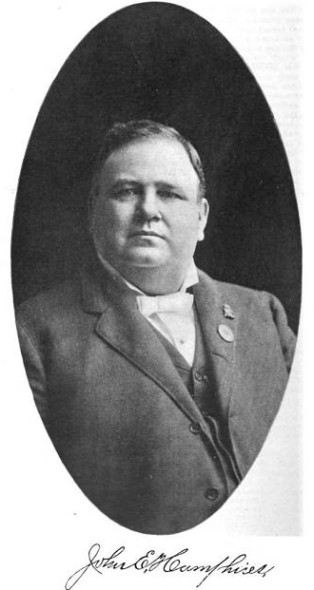

Judge Humphries, The Coast Oct 1903 page 140.

Judge Humphries, The Coast Oct 1903 page 140.

So what was the news?

The racist judge John Edmund Humphries was dead. The Seattle Times made him front page news for days, showering him with praise and memory. Odd that they forgot to mention that Humphries wrote the Ghent Bill, a 1911 attempt to make interracial marriage a felony in Washington State. He thought that it was immoral for whites and non-whites to marry.

They also ignored that he was attorney to A. E. Fowler, freeing him from a mental institution after he attempted to start a race riot in Bellingham. Fowler moved to San Francisco and became publisher of the illustrious journal The White Man.

Humphries was also the wizard behind the Asian Exclusion League’s efforts to send Asians packing. Humphries aborted his run for state Senate in 1910, focusing on spreading the white message. In raucous speeches he pleaded for us to consider what will become of our “children if you give the Pacific Coast to the Japanese, Chinese and Hindus?”

Thankfully, his charred remains were shipped back to Cincinnati.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Alongside his article was the story of Mildred Hill. She ran a lodging house at 2nd and Pine, and had finally been captured by police. Two weeks earlier a warrant was issued for her arrest in Tacoma, for hit and run manslaughter. She cut her hair, put on men’s clothing, and wandered the streets of Seattle. At last police were given a tip and tracked her down at a rented room.

The Times bookended that with a massive drug bust. $15,000 (340 Gs in today’s money) worth of opium was found in 189 tins in the closet of a room of the Milwaukee Hotel. The hotel, which still stands at Maynard and King in the ID, had previously been the scene of an opium shoot-out with police and smugglers. Opium was not illegal, but heavy taxation led to a brisk smuggling trade from Canada to the US. (This set the stage for alcohol smuggling a few years later. See this great series of CINARC essays.)

The Coup de Grace

Foremost in our park lovers’ thoughts must have been the headline at the top of the page, “EXTRA! Dynamite-laden scow blows up in Elliott Bay”. On the morning of May 30, one of the most fascinating and poorly remembered events in Seattle history occurred.

At 2 AM, a small barge carrying 15 tons of refined gunpowder went up, well, like a powder keg. It had been tied up near Harbor Island, but the shock wave shattered windows all the way up First Hill and lifted houses on Queen Anne Hill off of their foundations. The note in the Sunday paper was brief. Monday brought description of the chaos and confusion. On Tuesday, the first allegations were made about a man in Tacoma of possibly German background and his very manly wife who had gone missing the day of the explosion.

That’s the extent of the story that Paul Dorpat wrote for HistoryLink in 1999, before the Seattle Times was searchable by keyword. Now we can piece together the actual story and put it in context.

Germany had instituted an aggressive espionage and sabotage program in the United States. World War One had begun in Europe, but the United States still refused to contribute the lives of American soldiers. Instead, we sold munitions to the Allies, and embargoed Germany. As this CIA article describes, Germany was already secretly placing bombs on US merchant marine vessels in New York weeks before a U-boat sank the RMS Lusitania near Ireland on May 7, 1915.

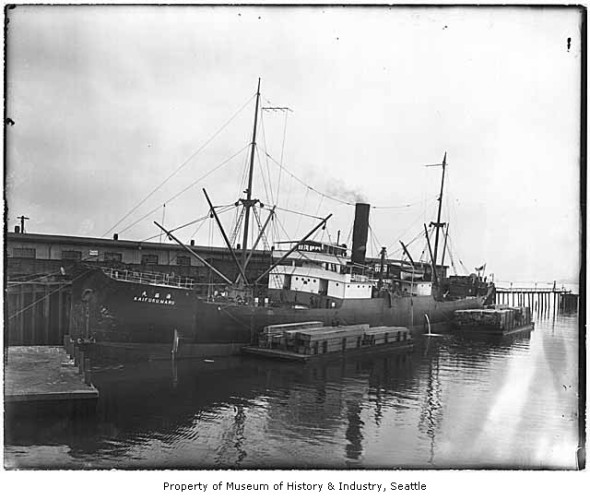

SS Kaifuku Maru, 1983.10.10541, MOHAI

SS Kaifuku Maru, 1983.10.10541, MOHAI

Meanwhile, a German agent named L. J. Smith infiltrated a munitions factory in California. Learning of a shipment headed to Russia to be used against Germany, he and his superior, Charles Crawford, traveled to meet it at Tacoma. Somehow they were stymied, as the captain of the Japanese vessel Kaifuku Maru got wind of the plot and refused to take the cargo. So the gunpowder ended up on a barge in Seattle’s harbor on May 30. They set a timed explosive and hopped on a train out of town.

Apparently it was British intelligence, headed by Tacoma-based Vice-Consul Lucien Agassiz, who cracked the case. His men tracked down more of the German spy ring. In July, Secret Agent J. E. Sweene cornered the head of the ring at the New Star Hotel in Seattle. Emil Marksz shot himself with a .45 revolver before he could be captured and questioned. It didn’t end there. The agents found dynamite under a railroad bridge in California, meant to destroy more of the Allies munitions. And the German effort kept on for months.

The CIA’s account of Germany’s World War One terrorism skips events on the West Coast completely. Like other online accounts, there are details of the U.S. Senate bombing, of the Black Tom explosion in New Jersey, but not Seattle. It’s missing from the Wikipedia list of terrorist attacks in the United States.

Maybe it was ignored over on the Atlantic coast back then. And surprisingly it’s been all but forgotten here today. But the bright flash and hurricane-force wind that ripped through Seattle was certainly on the minds of the strollers photographed in Volunteer Park on Sunday, May 30, 1915.

Catch up on Re:Takes

Head over to Flickr to see a larger view of this article’s Volunteer Park rephotography blend.

Did you miss the recap of Re:Take’s first year? Also, here are the last few Re:Takes on CHS:

What an interesting post! I’m glad to see that old photo, with one of the lily ponds in the foreground…I’m so glad those ponds, which were neglected for years, finally were brought back to life a few years ago. They are an important and beautiful part of “our” Volunteer Park.

Thanks, as always, for brining a photo to life. I appreciate the history and enjoy pausing – if only for a couple minutes – to reflect on what life was like in a different time.

This is amazing.

Thanks for another great window into local history! My dad has told me stories of Japanese espionage in the 1930s when he was a boy in Burlington, but this is the first I’d heard of German WWI activity here. I can’t help but be reminded of the SS Mont-Blanc in Halifax (Nova Scotia, December 1917), though the Seattle explosion was thankfully on a far, far smaller scale.

Interesting article, except there was no CIA until after World War II. Possibly files of the present CIA tell the story, but the U.S. spy agency was not called CIA back then. Take it from an elderly person who was around them.

Thanks Kay. The CIA article I link to is a modern history of terrorism, not contemporary to the explosion. I was trying to make the point that places where I’d expect the Seattle terrorist attack to be mentioned, it is completely ignored (because it’s forgotten).

Thank you~

I did a brief search to try to find what type of fish were in the pond originally, but couldn’t find out. I doubt koi/carp were kept back then?