Dotty DeCoster is a regular contributor to CHS on matters of Hill history. We last featured her work in this article about the St. Joseph Carmelite Monastery, An oasis of silence and prayer at 18th and Howell.

Dotty DeCoster is a regular contributor to CHS on matters of Hill history. We last featured her work in this article about the St. Joseph Carmelite Monastery, An oasis of silence and prayer at 18th and Howell.

Old ideas can work well, if they are outfitted with new technologies. That’s the message from one of Seattle’s oldest, and smallest, power generators: Seattle Steam Company. The old steam plant has been around since 1893 down on Post just north of Yesler, and it still operates, at least until the newest experiment of Seattle Steam (with a $19 million federal grant to assist) begins – generating electricity as well as steam, as it did when the company began. With an elegant new stack, rebuilt after the last major earthquake to landmark requirements, the old steam plant may become the new downtown district electricity back-up.

In the meantime, the not-quite-so-old steam plant between University and Union with facilities on both sides of Western Avenue, is generating steam with wood waste. Well, not today. Today the silo is being pumped out so repairs can be made to a part that wasn’t quite up to the junk in the waste that comes from Cedar Grove, Allied, CleanScapes and other sources. However, since last year the facility has four boilers, one of which can burn wood waste. The plant can switch between heat sources (diesel, natural gas, oil, wood waste) in a matter of some ten minutes or so, which makes is very responsive to fuel costs and also to load variations that might be related to disasters or weather events.

I had an opportunity to tour the plant with David Easton, vice president of the company, and the folks at Arcade. It isn’t space age technology, except for the Baghouse: a complex of filters that clean the emissions. The wood processing is pretty straight forward and tucked nicely into the historic coal storage area complete with tunnel to the plant. (A fair amount of coal used to be mined near Seattle, and it was the cheap fuel at the turn of the 20th century.) Seattle Steam is excited to be able to offer this fuel source to their customers who may be able to realize up to 50% reduction in their carbon footprint. (Wood waste burning is a closed carbon loop.) Also, LEED 3 includes district energy for the first time.

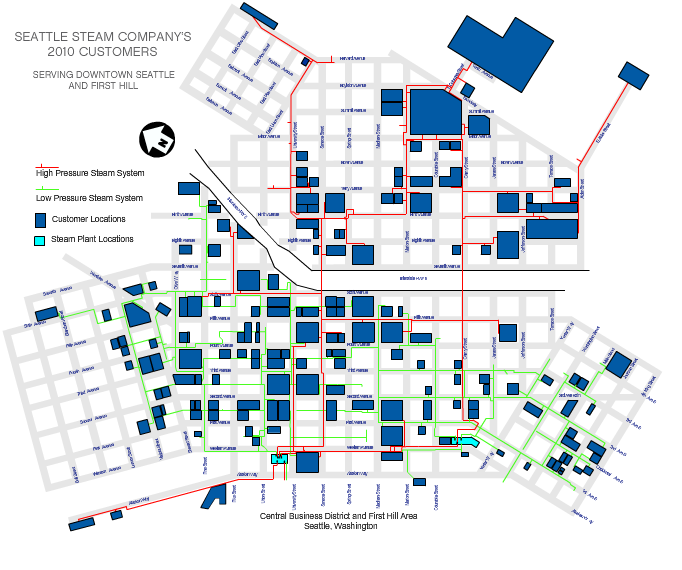

This may seem like downtown news. It isn’t. Since 1964, Seattle Steam has been serving the major hospitals: Swedish, Virginia Mason and Harborview, 24:7. Also Seattle Central Community College, Seattle University and a number of other places along the way.

This may seem like downtown news. It isn’t. Since 1964, Seattle Steam has been serving the major hospitals: Swedish, Virginia Mason and Harborview, 24:7. Also Seattle Central Community College, Seattle University and a number of other places along the way.

Walkers notice this. There’s almost always a little steam escaping from the hatch at the intersection of Harvard and E. Pike, also at Boren and Cherry. The steam is carried through a carbon steel pipes running from 3 ½ to 18 inches in diameter. There are two systems: one is high pressure at 140 psi and the other is low pressure at 15 psi. The hospitals like the high pressure steam because they use steam for sterilization and laundry. Lower pressure works for heat and hot water. Some of the pipes downtown are the original ones, likely not carbon steel 115 years ago. They last a long time because they don’t corrode. The piping is very expensive, currently something like $1,000/foot, so it is unlikely that there will be much expansion of the system. A good thing the pipes are underground and no one thought to tear them out when electricity went hydro in the 1930s and people thought we wouldn’t need local power sources anymore. If one is building near an existing pipeline, though, check it out.

Seattle Steam has a great web site and there’s a cool interactive map that shows who uses the system: http://seattlesteam.com